Welcome back to The Trenchant Edges, where we’re experimenting with a bit more freeform content into the weird subjects for the rest of August.

Remember, in September we’ll be moving to a more limited two-posts a week. One on Friday morning for subscribers and one on Sunday morning for everyone.

Oh, and you can still book a time to talk with me via zoom.

To justify today’s subject I’ll point to two quotes. One from Terence McKenna and one from L. P. Hartley.

“The Past is a Foreign Country” - L. P. Hartley

You should constantly involve yourself in cognitive activities, because taking these drugs is one of the major cognitive activities. And then, if you have a grip on human history - where the human enterprise has been, where it’s going - if you have been many places, uh, it’s easier to map. I'm, I'm reminded of- there's an alchemical aphorism. I think its attributed to Athanasius Kircher where he says, uh, ‘the oldest books, the farthest countries, the deepest forests, the highest mountains, this is where you must seek the stone.’ And what he means is, you simply acquire experience, because it is only in the acquisition of acquired experiences that you have a reservoir to draw on when you seek to make metaphors and analogies about, uh, the alien thing. -Terence Mckenna

And today we’ll be taking this advice to what may seem a strange place.

Those famous Greek Philosophers who started the *music swells* WESTERN PHILOSOPHICAL CANON.

Now, personally, I like to think of us as the descendants of the Sumerians, ‘cause they’re the ones who got the culture avalanche we’re approaching freefall with. Mixed with a bit of Egyptian science and engineering and ripped off by Greek pederasts.

I joke slightly, but it’s impossible to really discuss the canon without looking honestly at what was excluded from it. We won’t be going into detail there, but it’s undeniable that Greeks learned a great many things from their ancestors and neighbors.

Yeah, I’m gonna defend the Canon

With that disclaimer out of the way, I’m going to say something I think is obvious but needs saying.

No matter how obnoxious some people act about the canon and the *many* failings of its individual texts, they’re still important, useful, and enriching.

First, though, let’s define what I mean by the Canon.

I mean the surviving and culturally enduring “Great” works of writing.

The collection above starts with Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, skipping over fuckin’ HESIOD and runs down a lot of names you’ve heard before.

See the problem with defining this sort of thing? I didn’t even make it to line 3 before getting pissed. And I haven’t even made my pitch for you to read The Epic of Gilgamesh or Enheduanna yet.

My gripes aside, the point even of a flawed Canon is to point people to works that have been particularly influential for better or worse.

Often worse.

We’re probably going to talk a lot about Aristotle and, hoo boy, did that guy make some mistakes. And I’m not even talking about his most well-known ones.

I’m talking about the time he wrote down the argument that some people deserve to be enslaved because they deserve it and can’t run their own lives. The antediluvian ancestor to scientific racism.

Aristotle didn’t know that. He was just defending the system that gave him time to write philosophy so maybe we should be cut him a break?

No.

Not on that one.

Anyway, I’m not going to give you any of the more nebulous arguments for the canon. That they’re works that elevate and develop higher aspirations in their readers.

Sometimes that’s true. Sometimes they’re a collection of assholes bad ideas.

No, I have two simpler arguments.

First, you find bits and pieces of these works everywhere.

Second, the Canon provides a guide of thoughts other people have already had. This means you can skip a lot of wheel inventing.

You get the most leverage from older works.

I was once told, though I’ve never been able to verify it, that the ancient Greeks had a saying that went something like, “Wherever I go in my mind, I find Plato waiting for me.”

I know the feeling. When I began exploring the first two *ahem* modern philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, I kept finding out that ideas I thought were mine were invented by these dead Greek assholes thousands of years ago.

But thems the breaks. We owe an unpayable debt to our ancestors for building the ideas and infrastructure we’re now trapped in. And the only way we can deal with that obligation is to understand it all well enough to hand it to our descendants better than we found it.

(oops)

Misreading Plato

I have a confession.

I owe Plato an apology.

You see, I tried studying Plato alone and misunderstood the intent of his works.

I’m in good company there, sort of. Or at least a famous company. You’ve probably heard the word “Neoplatonism” before and part of what it means is a late antiquity misreading of doctrine into Plato’s dialogues. Most famously by Plotinus, an Egypt born Roman philosopher who is usually credited as the founder of Neoplatonism.

But on my last reading of Plato’s Republic, I discovered something that stunned me.

Socrates is not the hero of the Republic. He’s accused, repeatedly, of being a kinda unreliable narrator. Maybe not someone to take all their words at face value.

And at the end of Book One, he kind of admits that he’s just been bullshitting for the fun of it.

See, Plato was smarter than me or Plotinus. He was writing teaching dialogues to instruct students in a kind of rigorous skepticism. He wasn’t selling dogmas.

Philosophical dialogues are notoriously hard to write because you’ve got to fully embody multiple points of view, giving each their due, and it’s much easier to write multiple points of view when none of them actually make the points

After consulting with some other books, wiser sources than myself, and the podcast History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps, I came to a more interesting view.

Plato was really fucking smart.

His dialogues never really convince or settle on questions because the whole point is getting actual people from unconsciousness about the moral or intellectual complexities of a subject to a more conscious one.

A place from whence they might be able to dig themselves out of the ignorance they find themselves.

Now, even taking The Republic as a kind of staggered series of lessons in critical thinking rather than a book with an actual plan for a real ideal civilization, we’ve got a much messier and more interesting text.

This brings us to two points:

If we’re going to talk about Plato we’re probably going to have to hit the Republic book by book. It’s too important and there’s too much meat there to do anything else.

I bring this story up now because it illustrates the jagged downside of the, “Find the most obscure knowledge in time and space” approach: If you don’t understand the social and cultural context of a work, you’re likely to misunderstand it.

Personally, as a dilettante, I tend to run with simply expecting myself to misunderstand things and to rush in blind, collect whatever insights I can, and then do a deeper dive.

It’s probably more responsible and faster to just… find the context by reading the scholarship and talking with experts. But at my heart am a contrarian so.…

Let’s step back to why I think Plato’s Republic is important.

A younger me would simply have pointed to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave as maybe the most powerful metaphor for leaving one’s cultural assumptions to find the truth for yourself ever written.

The jaded cynical wreck who stands before you here knows a little better.

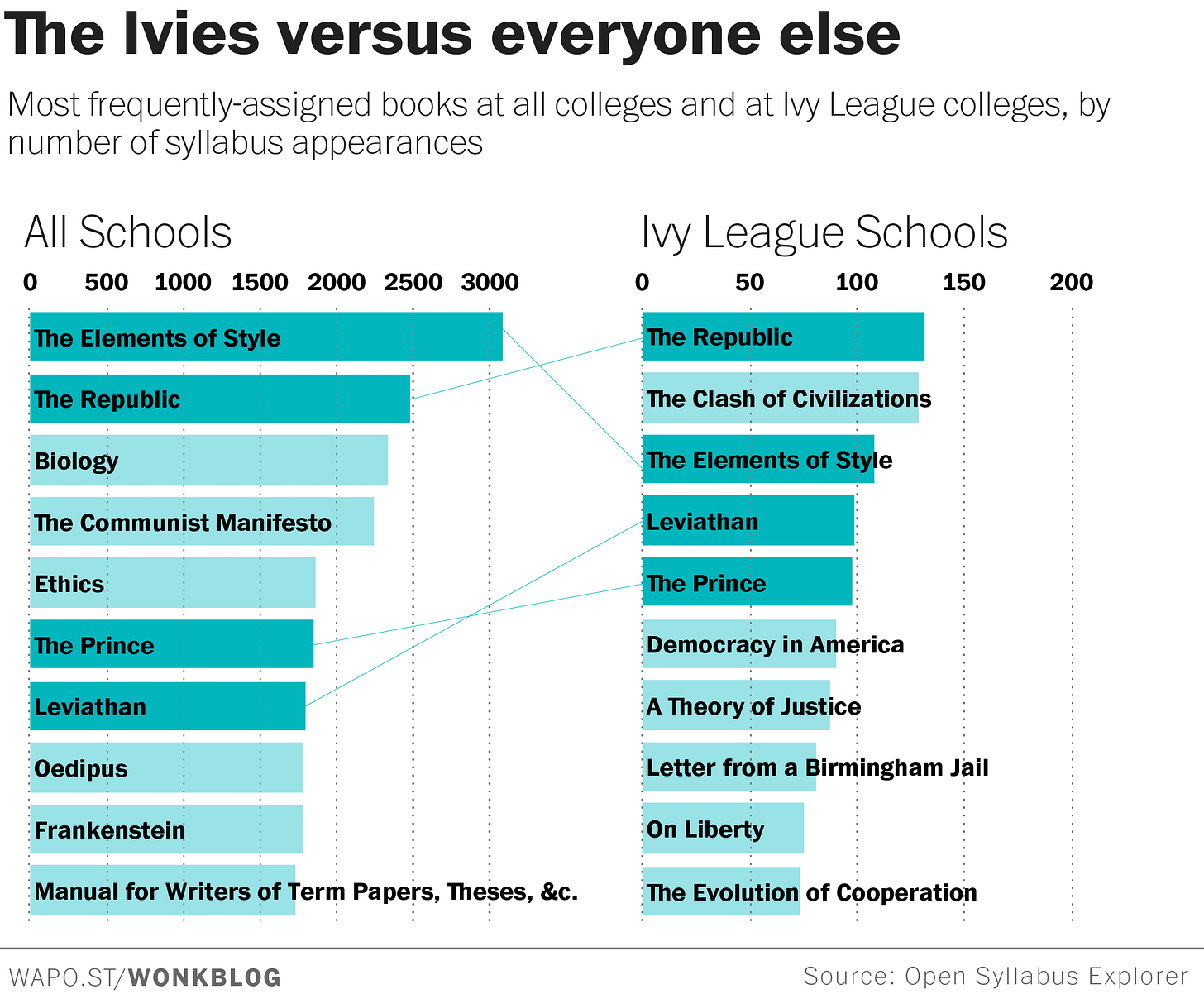

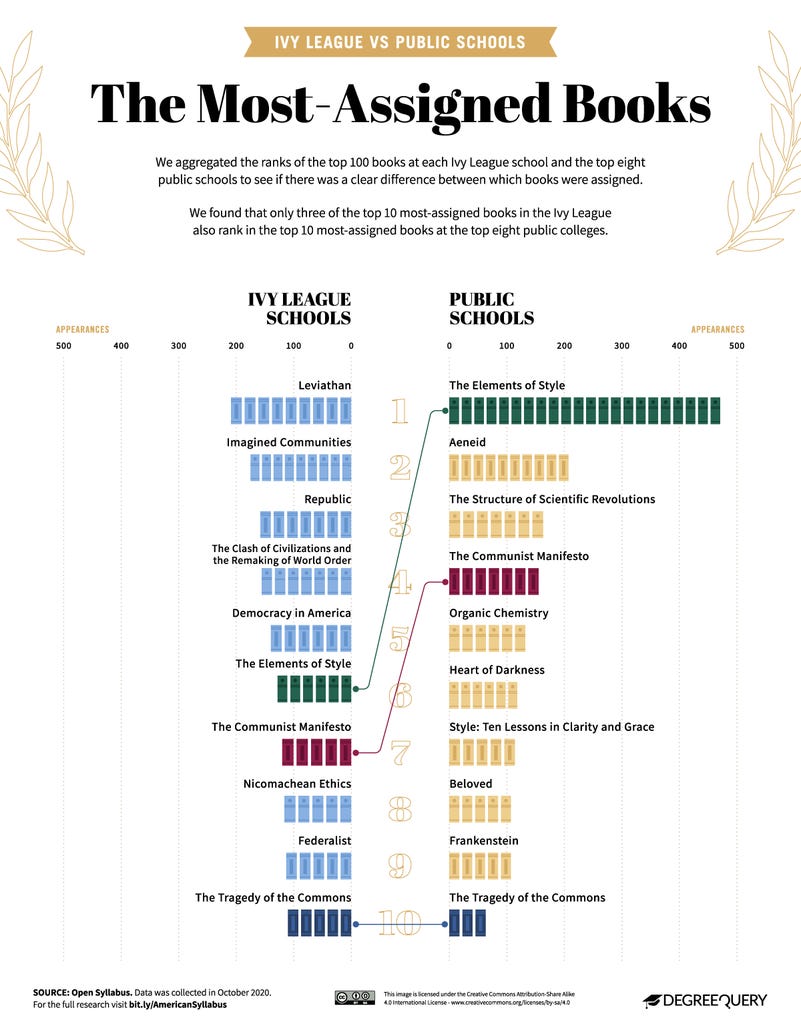

Let’s take a look at two charts looking at the differences between Ivy League colleges and either all schools or public colleges.

Now, you can look at the first in context here and the second here.

I don’t want to spend too much time poking through the details of these lists, as they appear to have been collected a bit differently.

There’s also a third group of people not pictured here, the 58% of Americans who don’t finish college and only read as much Plato as might take their fancy.

I bring up these three groups (Ivy League, college students/grads, noncollege students), because the overarching message of The Republic is kind of sinister as fuck if you’re teaching it to people who have been told they’re the smart elites who may have to lie to their lessers in order to preserve order and justice.

Let’s not get too caught up in the details of the dialogue here, but the short version is that the ideal city-state is ruled by Philosopher Kings because they’re the least susceptible to being corrupted by power and thus the best capable of ruling justly.

Part of how they exercise power is by promoting the Noble Lie, which is an untruth or partial truth that causes people to act better.

The Noble Lie is the cornerstone of all propaganda, conceptually. Most of the 20th century’s heavy hitters in the propaganda department would express roughly the same idea but cleverly rebranding it to better take credit.

Most famously is Adolf Hitler’s Big Lie and Edward Bernays’ Public Relations.

I don’t currently think Plato was trying to invent mind-prisons or indoctrinate future generations in how to build better mind-prisons. His treatment of this subject is far more nuanced and apparently prosocial than what I’m implying here.

But it’s the nature of knowledge to be useful for many purposes. And if students predisposed to seeing themselves as the educated elite might forget those nuances and carry with them the notion that sometimes you have to lie to poor people to keep everything working out for the best.

If nothing else it explains much of the culture of “journalism” since it got prestigious after Watergate.

This nasty complex of liberation and constraint is why the classics are important: They contain many important lessons, and some of them are very harmful.

And the evils they help generate and maintain are just as important as the good they may do.

Philosophy at its worst is naval-gazing and time-wasting.

Philosophy at its best is a gun. A weapon to defend or harm with depending on the user’s situation and intent. And like a gun, some of its consequences cannot be undone.

The bottom line is that whether you plan on harming or helping you better understand the tool if you expect to use it.

There’s another political angle I have for wanting to explore this subject more: Plenty of reactionaries fancy themselves lovers of the classics and we should not cede this ground to them.

Wrapping Up

So that’s my introduction.

As a project here, I’d want to focus on Plato first because he’s the first philosopher whose works we mostly have.

I know a lot of people are invested in giving that title to Socrates, but the Socrates we have is just a character in Plato’s stories. He’s the last vestige of an oral culture we cannot touch or engage with.

We can engage, pretty directly, with Plato.

While ancient Greek Philosophy has many more important and interesting thinkers, nobody else really has the clout of Plato and Aristotle.

And as those of you who read Monday’s piece on trust networks and ethos, despite his abhorrent views on slavery and his many bad opinions, I do think Aristotle largely deserves that position.

If y’all want me to continue this, I’d be happy to.

There are also plenty of other people outside the canon well worth discussing. I mentioned Enheduanna earlier and she’s a pretty amazing poetess as well as a princess (we think) and high priestess of Innana and Nanna.

But I want to focus on Plato and Aristotle because so much of our culture makes more sense once you understand more of their wake.

Entergaging Questions

Who else would you like to learn more about?

Have you read Plato or Aristotle? What did you think?

I am still onboard with a Plato/Aristotle investigation. I think there's a lot of valuable stuff there, but I can imagine it may not be quite as esoteric/weird as some folks want. I've read some Plato and Aristotle back in college. It's definitely the sort of stuff that benefits from discussion and explication, IMO.