Ghosts of the 21st Century Haunting the 20th [Trenchant Edges]

Estimated reading time: 8 minutes, 36 seconds. Contains 1720 words

Welcome back to the Trenchant Edges, a Newsletter about figuring out what kind of newsletter it is.

I’m kidding, almost. We’re about unpacking fringe ideas and seeing what’s inside.

Today I want to try out something a little different. There’s an essay I’ve been chewing on for a few years. It’s been more challenging thinking about than I expected because it’s sharply critical of two thinkers who have greatly shaped my own worldview, Alvin Toffler and Marshall McLuhan.

It’s the 1995 essay by Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron, The California Ideology.

So put on your Ray-Bans and turn on the Chili Peppers, it’s time to embrace that California Shit.

Or not. Turns out the California Ideology is real bad actually.

Whoops.

Note: I’d wanted to do this as a big single shot, but I keep finding weird digressions and I wrote this bit like a week ago so I’m just going to start publishing sections until I’m out of things to say

Heightening Contradictions

So, CI is a kind of anti-manifesto, an evocative critique of a heterodox milieu of beliefs from apparently different sources.

Barbrook describes it as a “critique of dot-com neoliberalism”. And it’s one of those essays that references so much that you could easily write several times as much as its ~8000 words on all the details.

There’s a short, 430-word section called The Myth of the Free Market where it sketches some of the ways silicon valley has been utterly dependent on public funding despite all of its rugged individualist posturings. Several whole books have been written on the subject.

And much of the manifesto is like this, begging for more details, and many people have expanded on it in the years since its initial publication. A quick look on Google scholar finds over 300 citations.

But I digress, the point of the California Ideology is a kind of third way of combining left libertarian ideas of renewed direct democracy and right-libertarian entrepreneurship within a faux-apolitical structure of technological determinism.

Its roots are in the hangover of 1960s counter-culture Hunter S Thompson eulogized in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Nixon’s victory closed the door of politics and so a ton of people were looking for an alternative and many refugees landed in tech.

The whole story of that transition is told in excellent detail in John Markoff’s What the Dormouse Said:

And even the cover of this book loops back to our theme: Steven Levy, a journalist who’s written extensively about the tech industry, is an editor at large at Wired magazine, the central publication of the ideology along with Mondo 2000.

So the idea is that many people disillusioned by the 60s and 70s ended up building tech in the 80s and 90s and they brought their baggage with them.

This brings us to where we need a bit of personal background.

Alvin Toffler and the Making of Me

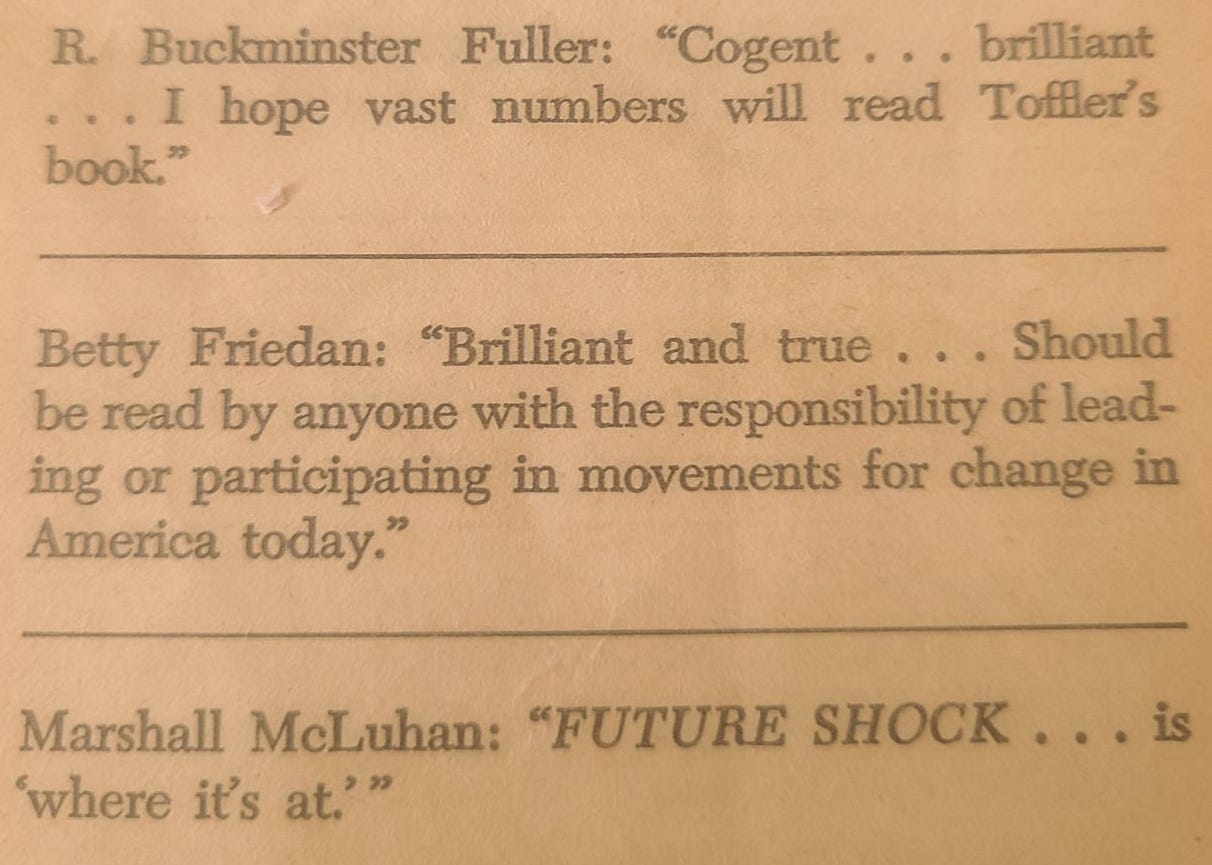

One of the first “real” books I read was Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock. I picked it up from my mom’s bookshelf in my junior year of high school and it blew my little mind.

Wild that a book about the future crashing into the present written in 1970 would be compelling to a nerd in 2003, but there you go.

Toffler’s thesis is that because the rate of cultural and technological change is increasing, people are increasingly tired of trying to adjust to it. A variety of culture shock, except for your own culture.

I don't really know why this felt like such a revelation. Maybe because this was the peak of my personal depression and the thought that change was even possible was exciting.

It also introduced me to the idea of futurism which very much inspired a lot of my reading since then.

It was also one of the densest books I’d read up to that point and the hard reading made the understanding I got from it feel more important than it really was.

So now we need to talk about the rest of Toffler’s legacy.

FutureShock laid out a messy future where things would get better but we could easily lose ourselves in the process. In retrospect, the influence of Friedrich Hayek is pretty clear in the last chapter especially, warning against technocrat elites using their superior organizational skills to monopolize the benefits of technology.

And Toffler’s ties to the right wing would only grow. In the late 80s and 90s he formed a long-lasting friendship with Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich.

We do not have the time today to discuss Newt in detail but I’ll just say a thing: More than Nixon, more than Reagan, more than Bush(s), more than Trump, Newt Gingrich is the man who invented the modern republican party continuing its decades of shit.

Without his regimenting the party and adopting an aggressive post-cold war stance we simply would be in an entirely different place.

Point is, dude made his money consulting for big business and helping build the coalition of ideas that make up the Californian ideology. And he was far from alone there.

So Toffler helped bring in both the ruling ideology of the tech industry today and the rise and prominence of one of the worst people in congress. Great. Love it. No notes.

*sigh*

In retrospect, it’s easy to spot the deeply reactionary assumptions of Future Shock, though I think it describes a real social force. I think a ton of the appeal of conservative culture war issues is trying to stop at least *something* and you’re certainly never going to stop technology or economics. So loudly haggling about pronouns, immigrants or civil rights becomes a proxy for everything else frustrating.

But I… redigress? Undigress? regress? I don’t know. whatever.

Hypermedia

I guess we need to talk a bit about hypermedia as a concept.

We don’t really need a definition or explanation since you couldn’t have found this obscure corner of the world without deep familiarity with it, but it’s one of those archaic attempts to help people conceptualize their shit.

Like the INFORMATION SUPERHIGHWAY, always my favorite.

But the TLDR is hypermedia is an extension of hypertext into other forms of information: Video, audio, etc. OK, that wasn’t useful, but just imagine the way wikipedia works but extended with embedded video/audio that are also hyperlinked.

The Internet as it is functions that way, but the actual linking isn’t really done very well. And is highly variable what can and can’t be linked depending on the website.

The idea was coined by Ted Nelson along with Hypertext as part of his attempts to conceptualize a computer usable by regular people and not just programmers in 1965. You can read the paper here and it’s fascinating. Nelson starts of by quoting a chunk from Vannevar Bush’s 1945 essay As We May Think.

And now I feel like the rambling nature of this as I unpack new and different rabbit holes and try and turn them into coherent content at least demonstrate *how* Hypermedia actually functions.

The point is, like Television, Hypermedia was supposed to be this hugely useful tool to educate people and it turned into something very different.

Unlike TV, Hypermedia’s locked into the kind of skinner box nightmare of Shoshana Zuboff’s Survelience Capitalism.

These are ways in which the techno-optimism of the California ideology kind of breaks down. The janky rocks of reality & the restructuring power of capital accumulation.

Where broadcast technology really supports an orthodoxy, particularly in its early years before the cost of broadcasting came down enough for their to be tons of channels, hypermedia’s natural form of organization is the cultural milieu.

Because everyone’s experience is nonlinear and disciplined by personal interest and the incentives of various infrastructure players, and heresy becomes the new orthodoxy.

Slap that onto an attention economy and you build a machine that generates hot takes by rewarding the hottest takes with the most attention and you ensure everyone’s constantly refragmenting & forming new social groups.

And if the social context of the people who start using that technology is a mix of paranoid and heady attempts to explain and resolve the contradictions of a global empire that can’t admit it weilds immense force to ensure compliance and you’re bound for a skewed experience.

The shared foundation of communities is the remix and reaction rather than shared experience or belief.

Of course, all this happened long before the World Wide Web, but now it happens everywhere and at the speed of thought. Or at least the speed of reflex.

Conclusion

Terence McKenna once said something about computers being drugs and he wasn’t wrong. We’re all high as shit on this stuff and it often seems like the only way to even understand what that’s doing is to unpack old stories people told about what computing was supposed to do for us.

Which is kind of my pitch here.

Of course, perhaps I should simply suggest we all log off and “touch grass” as the kids say.

But I don’t think that’s enough these days. We need a sense of the vector we’re all traveling down this path together.

I go back to a line from McLuhan:

“There is absolutely no inevitability as long as there is a willingness to contemplate what is happening.”

And then, somehow, we need a way to pick a better future than the one we let them dream up for us.

Maybe that’s a bridge too far but I’m still gonna be here throwing myself against it.

Anyway, I think I’ve gotten most of my big digressions out of the way for this essay.

I’ll see y’all tomorrow with the next chunk of it.

-Stephen

If you found this piece interesting or useful, I’d really appreciate it if you could share it around or become a subscriber.

I provide this on a value-for-value model. I hand it out for free and ff you think it was worth your time and attention you can contribute if you think it’s worthwhile.

Right now it provides beer money for me, but if it made more I’d be able to devote more time to it.

Anyway, thank you for reading this far and I hope to see you again here tomorrow.

-Stephen