Nothing Unannounced, Terence McKenna Fumbling for a Theory [Trenchant Edges]

Welcome back!

This is the Trenchant Edges, a newsletter about taking weird ideas seriously.

My name is Stephen Fisher, your host and research junkie. I’ve been hooked on weird ideas since my father made the dubious choice of letting me watch the History Channel in the 90s.

Contrarian thought is rarely systematic and almost never rigorous, but where they fail at replacing the edifice of modern knowledge as perhaps intended, they often do contain valid insights and useful perspectives on the gaps in mainstream ideas.

It’s my observation that in 2021 we’re looking at the United States where the institutionalized sources of knowledge and authority have kind of stagnated into technocratic incompetence.

Our models of the world are out of date and the people in charge don’t seem to be super interested in fixing this, in part because of the benefit from the errors involved.

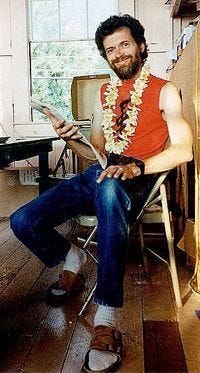

So, Terence McKenna and his Brother

It’s critically important that we recognize that while Terence became the famous speaker for, uh, covering the content of the drug experience, his most famous moment at La Chorrera was actually driven by Dennis McKenna’s wild ideas.

And their book, The Invisible Landscape bears this out.

The first section (which I foolishly thought was the second over the weekend) is about convincing you that this crazy idea they’ve developed is worth discussing enough for the time it takes.

There are seven chapters in this section and we’ll be dealing with the first 5 today.

The first two are musings on the midcentury ideas of the tribal shaman and schizophrenic, two artifacts of 19th century academic thought. The first being a western colonizer idea of a kind of common social role in many nonwestern cultures: The medicine man/wise woman/psychopomp/magician, a kind of mix of folk science reaching towards the supernatural.

Since Terence’s time anthropology has spent some considerable time rethinking its descriptions of these roles and recognizing that they universalized a very specific cultural practice in ways that muted the vast differences in cultural expression. It’s messy ‘cause the term’s still used but that’s the way of sincere inquiry sometimes.

Similarly, Terence’s ideas about schizophrenia are 60 years out of date here and most useful to illustrate the contrast between how traditional cultures have contextualized certain kinds of mental illness versus the “scientific” cultures.

This has caused considerable problems as it’s easy for someone with serious mental illness to declare themselves a shaman and ignore any other kind of approach that might help them find more balance. In most shamanistic practices I’ve studied, there’s a substantial canon of cultural knowledge that comes with the spiritual illness that Terence focuses on.

Beware of false integration is all I’m saying here.

The bulk of our interest here comes towards the middle sections.

Holographic Minds, the physics-mind connection, and that one chapter that kind of sucks.

We’ll start with the “sucks” chapter.

It’s called Organismic Thought and it’s largely a retread of Albert North Whitehead’s Process Philosophy which is rad and good and you should look it up on your own time.

The hardest problem with being a contrarian intellectual is you always need a methodology to explain why the mainstream scientists got it wrong.

Terence avoids the easy answer of calling it a conspiracy and attempts to work through some of the toxic 19th-century assumptions that still polluted science in his day. Such as leftover Cartesian dualism, determinism, and various methodological flaws in pre-quantum physics.

I say this sucks because it reeks of “undergrad philosophy student applying a shallow understanding of physics writing a paper on the implications of those physics to philosophy”, a genre of category error that’s unmistakable after your second or third exposure to it.

His criticisms aren’t necessarily wrong here, it’s just that even while he was writing this science was, in fact, addressing those issues. Reading it in 2021 just feels like he’s complaining that Chemistry once explained fire with a mystery substance called phlogiston before Antoine Lavoisier figured out there was oxygen in the air.

We’ve talked a bit about the next two chapters: Towards a Holographic Theory of Mind and Models of Drug Activity before.

I don’t really want to focus on their exact content so much as their structure and rhetorical value.

TLDR: Terence is remixing some partially borrowed concepts from neuroscience and physics to create two complex arguments.

The surface argument is a causal chain between Electron Spin Resonance, a kind of subatomic particle magnetic relationship, and the way the mind constructs the universe.

The implicit argument is to create an illusion of technical density the laypeople his books are marketed towards will recognize as more knowledgable than they are, but be difficult for them to disprove without developing real expertise. Which is a lot of work.

The latter might seem harsh but it’s SUPER IMPORTANT we talk about it, because it’s an absurdly common move. It’s easy for someone with a little knowledge of jargon to spin a web of accurate sounding pronouncements that only someone with at least as much knowledge can untangle.

We’ll be coming to that if I ever follow up on Reflections on Far-Right Propaganda as almost every fringe right-winger with any technical knowledge plays this card.

So let’s go back to #1. This whole section is about building enough plausibility that when Terence tells you he and his brother tried to bring about the end of the world by weird singing to transform harmine into a superconductor capable of bonding with DNA and allowing thoughts to recreate physical reality, that you don’t just laugh in his face and say, “You’re not even wrong”.

(a thing that did happen to him when he tried to explain his ideas to a Berkley scientist in the wake of the experiment)

So, not to get too Abraham-Hicks or the Secret on you, the idea here is that by taking advantage of certain processes in physics (ESR, superconductivity, etc), thoughts can become things.

We’ll be seeing how this played out in their experiment more tomorrow, but I supposed I don’t have to tell you that history didn’t end in 1971 and we were not liberated from the tyranny of natural law.

Anyway, we’ve covered the sections a bit before here and here and the reason I keep running over them is that there’s just a lot to unpack through the technical jargon. I’m no more expert in any of these fields than Terence is so it can take a while for me to really parse what he’s claiming.

All this is part of what I mean by taking weird ideas seriously. An actual scientist would recognize the faulty assumptions and move on to more obviously fertile grounds.

I’m staying to critique the architecture because 1. I think there are some important pieces to learn from it and 2. I kinda feel someone ought to appreciate the work put into it.

It’s a huge, magnificent edifice Terence tries to build here.

And we’ll get into why it’s Terence who tried to build it and not Dennis when Dennis was the one who came up with all that superconductor and ESR nonsense.

Be seeing you tomorrow for that.

Hey Stephen, I just subscribed yesterday and I am in awe. I am curious, do you do writing for hire? If so can we get in contact?