Rethinking the Conspiracy Wars [Trenchant Edges]

2,500 words and about 10 minutes to read.

Welcome back to the Trenchant Edges, a newsletter hastily created while hastily researching other things.

Today we’re taking a swing at a subject I’ve done a few times already: Cutting through the bullshit around what makes some speculation illegitimate.

I have a sense of the bigger picture.

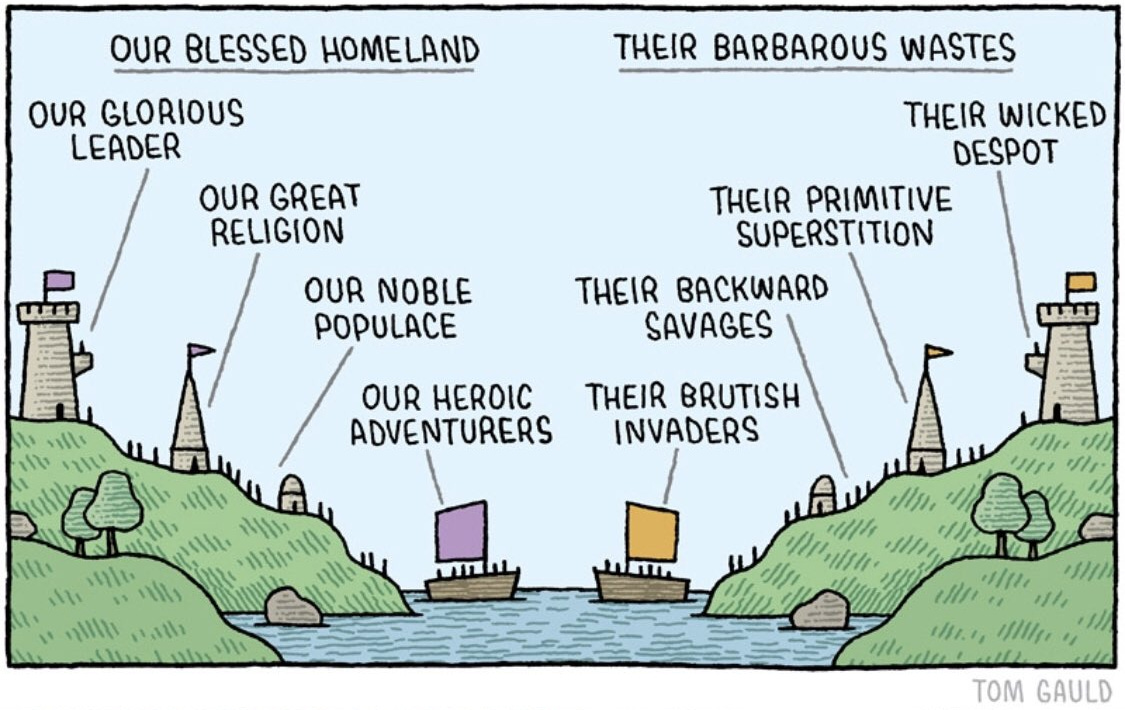

Conspiracy believers often say that so-called legitimate sources can’t be trusted. Their skeptics/debunkers/commenters say believers can’t be trusted. And things quickly collapse into bickering about the argument itself. You’ve probably seen a thousand times.

If we’re sticking to the broadest outline we can easily see both sides are right, but the second we look a little closer things get rough for the believers. Graham Hancock is right that “mainstream archeology” often fails their lofty ideals.

He loses me by trying to leverage that fact as evidence of his very idiosyncratic ideas about Atlantis.

And maybe more importantly I don’t think any archeologist would disagree with that statement. The field has been trying to do better for decades.

This battle has been going on for a few hundred years without any sign it’s slowing down. These days it’s usually framed as, “What is or isn’t science?” or the demarcation problem.

Picking a side and trying to bludgeon the other one isn’t going super well. But I think we can slouch towards a higher perspective that integrates and expands both of them.

We just need a brief detour.

How the Church Became the Academy

With a disclaimer that this is a complex and thousand year history I don’t know in depth I’m reducing to a few paragraphs because it really does seem to frame the whole subject. If you’re a scholar who knows more of this I’d love to talk. Also, it’s focused on Europe because that’s already too complicated.

For almost a thousand years Universities have been running in Europe. The oldest is the University of Bologna that got its start, allegedly, in 1088. Oxford was founded a few years later and both initially mainly produced priests, lawyers, and most beloved of all, priest-lawyers*.

*Oversimplification

As time would go on bit by bit, people started studying other things. There was that whole Protestant Reformation and centuries of religious conflict that have only sort of ended in the modern era. But people by large decided that secular institutions were more stable and respecting the freedom of their communities than religious ones. This was true for states and schools alike.

There was also a bunch of colonization which accelerated new ideas and provoked new backlashes and reverse backlashes. Lots of people died, some people got rich. We did slowly learn a lot more about the world. “Yay” modernity, I guess.

Look, it’s been a busy thousand years.

Scientific methodologies developed as secularism became the norm. This didn’t mean the academy stopped doing awful things, they just did different awful things. Eugenics and other race science are easy answers.

By the time we hit the first world war, science had become integral to both economic and military success and with those successes its prestige skyrocketed. Causing nations to shovel more money to it.

All of this set up a world where the social position of Priests kind of rubbed off on Academics. At first this was because Priests and Academics were mostly the same people. The priest-lawyers became priest-scientists. Over centuries this became less true and we just ended up with scientists. But academics retained some of the elevated social status traditionally accorded to priests or high ranking guild members. To this day, “Doctor” is one of the only formal titles remaining in society.

And by the end of WW2, the scientific expert had become the technocrat. A new priestly caste of Scientist-bureaucrats who would rationalize society and who promised to benefit everyone. (rimshot)

Again, vast oversimplification.

But this is the world that conspiracy theorists reject. And they should. It sucks. We didn’t get maximum efficiency for everyone, we got a few decades of brutal imperialism to pay for social bribes in the first world followed by breaking down those systems because they got in the way of the richest people in the world getting richer.

The vanity of this system was never unchallenged. But we’re something like 80 years into the world system hitting crisis after crisis that experts didn’t predict and only understood in retrospect and a lot of people being understandably pissed about that.

And that’s without going into the many, many factions who wanted to shape the world in their own image.

In short, all this is annoying as hell and many people have been misled by those whose social status has been elevated by their so-called expertise. To pick the most famous example in my mind: The allegedly left wing New York Times were the loudest and most influential press cheerleader for George W Bush’s illegal Iraq invasion.

We could spend all day giving examples.

After WW2, the US attempted to use mass media to induce a shared consensual reality for most of the world. Academics were foot-soldiers and strategists in this global plot.

Skepticism is more than justified.

But the story doesn’t end there. Skepticism isn’t a magic formula for virtue. At best it’s an invitation to develop it.

The Failures of Debunking

Let’s get the debunking thing out of the way. Most debunkers don’t understand context and thus only ever attack symptoms instead of the underlying systems that produce social conflict and paranoid ideation.

I have little sympathy for what passes for skepticism in the US. It’s not an accident that the most prominent group of “skeptics”, the New Atheists, largely ended up just shilling for the very people they used to debunk. See “Cultural Christian” Richard Dawkins for the most famous example.

One source of the confusion is a technical point of of logic. Debunkers rarely distinguish between internal and external consistency in the logic of the people they’re debunking. Usually they skip to cheap shots/insults for the entertainment of their audience and shame of their targets.

Internal consistency is about how coherent the reasoning of an argument is within itself. Are their flaws, gaps, fallacies, or other errors in logic?

External consistency is about how well an argument applies to the real world or other relevant evidence.

Another way to put it are the questions, “Does the argument make sense in itself?” and “yeah, but is it real though?”

Now, lots of conspiracy slop accounts don’t even make it through internal consistency because of the context we’re going to get to.

But every one that does is fundamentally rational. Rationality doesn’t mean correct, it just means that the logic works within its own terms.

Mathematics famously lets you create logical systems that do not apply to the real world.

This is why science had to be invented: You can be rational and wrong. It’s easy to. To get really good knowledge it has to be tested in the real world. We call that empiricism. The scientific method.

Debunkers making this kind of error hide the actual process of reasoning and thus make it harder to identify the actual errors involved for anybody. But this doesn’t matter because they also usually misunderstand the context. There are layers to error here.

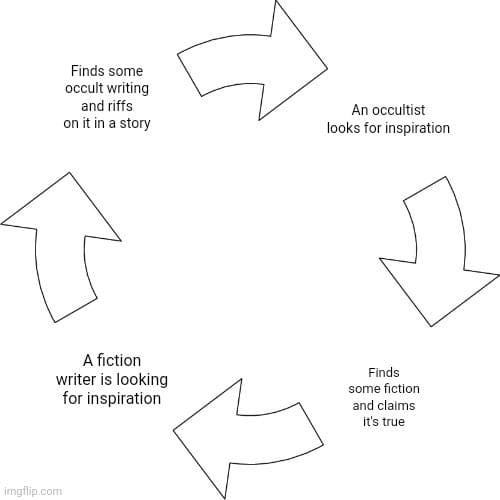

While many conspiracy theorists do have specific (and mostly awful) political projects they’re advancing, most of the conspiracy content online right now is pure storytelling. Sure, it carries ideology and implicit beliefs and is often useful to those political projects but the goal is just to harvest attention for commercial and ego purposes.

Commercialized folklore isn’t a scientific paper. It’s appealing to the frustrations and preconceptions of a mass audience for profit. It also acts as a radicalizing feedback loop.

Oh look, it’s our old friend the bullshit cycle.

By targeting logical errors, debunkers often miss the bigger issues and structural forces that create the discourse. Plus the actual motivations that bring people into conspiracy spaces.

In fact, debunkers are often engaged in identical social activities as conspiracy theorists: Policing the boundaries of trust within their social groups, crystalizing ingroup belief, and attacking perceived enemies.

Even if they’re technically right, as many are, the fact they’re also enforcing social boundaries makes them less trustworthy and less effective at fighting the irrationality they believe they’re opposing.

It’s kind of a problem.

All this means that even if a conspiracy theorist wants to engage rationally in good faith with criticism, it’s much harder than it could otherwise be.

Yes, some won’t ever act in good faith. But many people do sincerely believe they’re finding secret truths.

The Virtues of The Conspiracy Theorist

If we step back and view Conspiracy theories as a social force, we can see a few things worth knowing.

Conspiracy theories often correctly identify social problems.

They’re useful for holding together political coalitions.

They simplify complex interactions into stories.

By personalizing systemic forces they make organization harder

Antivaxers, for example, are correct to identify that Big Pharma’s profit-motive isn’t trustworthy. They’re much worse at understanding why or offering remedies.

This makes them vulnerable to people offering quack cures with the exact same conflict of interest Big Pharma has and none of their strengths.

Andrew Wakefield is a perfect case study here: The man kickstarted modern vaccine hesitancy by faking research to create the grounds for a lawsuit. He’s exactly the doctor antivaxers think run Big Pharma. But they love him!

And eventually the medical profession rightly ran him out of town for his crimes. It just took a decade longer than it probably should have.

But I don’t want to focus on the frauds here because their malfeasance can distract from the sincere thing I think most of the people interested in conspiracy theories are trying to do. Let’s distinguish them from the influencers with a commercialized folklore business.

Conspiracy consumers are trying to make sense of a world they know is lying to them with the tools they have. They are certainly guilty of many of the same motivated reasoning mistakes, bad faith framing, and outright racism as theory influencers are.

But their investment is rooted in identity and social group, not financial interest.

Conspiracy theorizing is kind of just a normal process of the human mind. We all suspect additional motives for actions of the people around us.

What gets most people into trouble is when they develop an aversion for a group of people, often a political scapegoat, and start looking for reinforcement of those beliefs.

In reinforcement they change how they relate to different sources. What groups get skepticism and what groups get a cognitive free pass.

It’s this shift that marks someone going from a passive interest in fringe ideas to a conspiracy believer.

And this is the cognitive process that pro and anti-conspiracy influencers compete over.

All this happens under conditions where any time spent thinking or researching comes away from either working for money or leisure/social time. So everyone’s making scarce choices about how to engage with this kind of content.

In practice that means spending a lot less time on skepticism even if they want to learn.

But I promised you virtues, didn’t I?

I meant it too. In the abstract conspiracy theories seem like a fertile ground to develop all kinds of worthy qualities.

Let’s do one of those internet-friendly numbered lists

Skepticism of Authority

Openness to New Ideas

Independent Thinking

Resistance to Peer Pressure

Seeking Transparency and Accountability

These are all ways conspiracy theorists see themselves and their ilk and it’s not completely out of line.

It does take the courage of your convictions to stand up in a room full of people who don’t believe 9/11 was an inside job and demand they take that idea seriously.

It’s tempting to “But” this because, well, that’s how I feel. Since Occupy Wall Street I’ve said it: If 9/11 truthers didn’t exist, the feds would have to create them because they’re were so disruptive of any actual organizing.

Conspiracy believers usually have good intentions getting into the field, at least when they’re not nazis. Unfortunately the cultic milieu does not treat them well on this point.

Trading which ingroups you uncritically support is not a good recipe for achieving any of those virtues. And that’s often the price for joining communities built on contrarianism.

This too is a normal function of human thinking in social situations. The line between criticism and attack is awfully thin on a good day. And we all want to defend those we care about, ourselves included.

Institutional prestige and authority are poor replacements for real relationships of trust. Some of the dumbest and least trustworthy people I know have PhDs from Harvard.

But we live in a media environment that demands we trust a lot more than we should and doesn’t really give us good alternatives when we don’t trust. But that’s another essay.

The question I keep coming back to is, “What would change these dynamics?”

Where Is This All Going?

On a civilizational level, I think European-linked cultures are slowly recovering from the harmful and invalid authority of the church in controlling flows of information.

Academics are a poor replacement for priests in most social situations, but long term I’m hoping they’ll end up as a transitionary social form to something that generates robust expertise without the ivory tower elitism.

I don’t really have a clear idea of how that will work or what it will look like but I see signs of it all over academia as frustrations with administrations run by MBAs managing what amounts to a hedge fund with education and researched themed public relations department mount.

Likewise, media consolidation of both broadcast and independent media has made having reliable journalism much harder.

These have never been institutions to trust. The 20th century saw lots of experiments in objective and subjective academia and journalism with lots of dubious results on both sides.

I believe there’s a synthesis somewhere in the future.

But we’ve got a lot of swamp to crawl out of first.

Wrapping Up

The thesis I’ve been dancing around this piece is that media has successfully disarmed the revolutionary potential of skepticism towards intuitions towards scapegoats.

It’s not a partisan issue, though it is worse on the right.

Conspiracy theories provide a release valve where people who might do things that break the system can be be siloed where they’re usually harmless… unless they take political power.

Which, you know, they have in the US.

We started today with a recognition that what happens at the boundaries between “mainstream” and “fringe” happens in a context that needs to be understood before the conflicts make any sense.

I suspect this topic has another essay or two in it. There’s a bunch of theoretical pieces I want to bring together before it’s done.

Would love to hear what you think.

See you soon.

-S

Thank you so much for this. Cant tell you how much I loathe debunkers and professional skeptics. They never hold themselves to the same standards by which they critique and ridicule others.

Great essay. You're right that both sides are policing trust, not investigating why trust collapsed. But here's what gets skipped: institutions didn't get corrupted. They optimized past their own error-tolerance. That's not a conspiracy. That's just what systems do before they break.